What today’s founders can learn from William F. Buckley

A few elements of the entrepreneur's DNA

It might just be a consequence of who I spend my time with, not to mention my job, but the word “founder” immediately prompts the thought of a new technology company. Perhaps because most startups are in the tech industry these days, but the word did not used to have such a tight association.

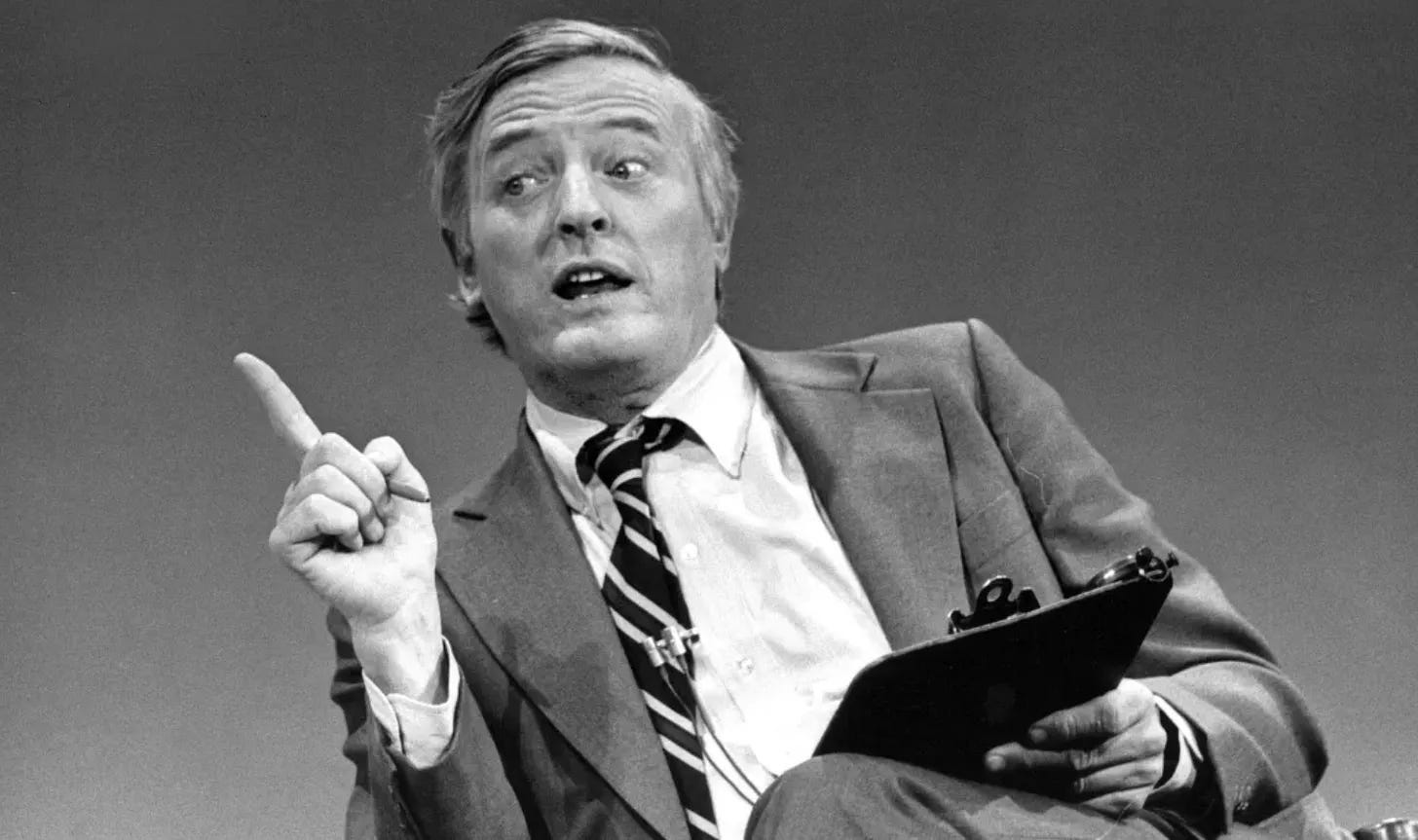

The other week, law professor Cass Sunstein wrote about his admiration for William F. Buckley, who founded the National Review magazine in 1955. Buckley was a trailblazer for conservative journalism, but political leanings did not prevent admirers from across the aisle. He was exceedingly likable, especially as the host of his famous Firing Line television programme, where he moderated weekly discussions on the issues of the day.

Sunstein wrote about certain qualities possessed by Buckley which formed his character and public persona, further detailed in the new biography by Sam Tanenhaus. Even though he started a literary magazine, Buckley shares many of the same traits as today’s tech founders, which can perhaps unlock a few of the reasons why his legacy has endured long after his death, and a pattern of behaviour in those who want to build something new.

Buckley wrote his first book, “God and Man at Yale”, after he graduated college in 1951. This is a typical mark of a founders – they start young, and worry about the refinement of their ideas later. In an interview with Charlie Rose near the end of his life, Buckley notes that it was a vertiginous experience to re-read his first book aloud. He thought it was terrible. As you get older, “you become more exacting of your own performances,” he says. At NY Tech Week recently, the DF team remarked they had met many founders (and aspiring ones) who were still in college. Such early ambition is a common strand of the DNA in founders, and a lesson from Buckley would be to not worry too much about what you perceive to be any early blunders. You can recover from them, and your better work in the future can eclipse the work at the start of your career. Even more, what you may take as underperformance can inspire others, as Buckley’s first book did with Sunstein.

Another characteristic of founders is a disinterest in the status quo. Buckley had no wish to attach himself to the pre-established credibility of other institutions. Instead, he saw a gap in the world he thought he could fill, and built an ethos which still lasts today. This approach requires some hubris, sure, and a bit of disagreeableness. Self-belief can stem from many places, including internal motivation or a moral obligation to the world. Additionally, these attitudes require a significant dash of risk taking, which has been thought to differ across cultures, but it is not purely an environmental condition. Previous research on tech founders found that “serial entrepreneurs were more likely to succeed than first-time business owners”, lending credence to the seemingly irrational advice to keep failing. Founders seem to carry these formidable attributes within themselves as features of an identity which forms an entrepreneurial spirit.

Lastly, there is something to be said for accessibility. Sunstein shares that he wrote Buckley a letter when he was young. “It must have been embarrassing, fawning, idiotic. And you know what? He responded. He wrote me back! I kept that letter — handwritten, as I recall — in my drawer of sacred things.” These stories never cease to leave an impression on me. I sometimes slouch into a melancholy reverie, thinking that the years we spend on our screens now dwarfs the time we all have to execute a personal gesture like that. It might seem impossible to reach people of a certain stature, but founders tend to be a breed that will try to make those meetings happen regardless. The world is much more connected than we might think, as proven recently by Zehra Naqvi, founder of Lore, who got to meet with Bob Iger to discuss the ideas which fuel her current project. The generosity of time given from one generation to the next provides oxygen to an optimistic stance towards the future. Buckley, it can be reasonably assumed, believed this profoundly. As Sunstein remarks, “All his life, Buckley was focused on young people and college students in particular”.

“He liked people; actually he delighted in them,” Sunstein writes about Buckley’s personality. “He connected with them. He wanted to make them laugh, and he liked it when they made him laugh. He didn’t hold their beliefs against them. He had a rare gift for friendship, and he cherished and kept his friends. (He hated losing a friendship, and he almost never did.) And he was not only full of zest; he was also a kind and good person.”

In the age of technology, this is a reminder to keep in circulation. An idea can only go so far, but people take it to its full potential.

Which other figures from history and culture do you think could provide some unlikely inspiration for today’s founders? Let me know who I should write about next on jonathan@digitalfrontier.com.